It's true that we're all only ever passing through this world, but part of being alive is that magical process of making it our own. ROB COWEN Common Ground

I love books, but I'm not precious about them. Although books seem to collect around me, I don't consciously collect them. Books pass through my library and life like people: fascinating certainly, often memorable, even life-changing — but one moves on to the next thing. I lend books, borrow books, sell books, give books, am given books, chuck books, even lose them. I have few fine editions with polished spines. Books on my shelves are there to be read, not to impress or gather dust. No doubt this cavalier but rather liberating attitude comes from my previous career in publishing sales. I used to get scores of free books by post every week for many years. I really didn't know what to do with them. Some I sold or gave away. Others I kept, thinking I would read them later — but I hardly ever did. I had far too many books of my own choosing to read!

At some stages of my life I've read omnivorously. At other times I've not read much at all. During my recent trek along the Via Francigena I packed only a guide book. But, of course, I read lots of other things along the way: shop signs, marker posts, graffiti, newspaper headlines, snatches of magazine articles, random fragments from the Bible in churches, words of nonsense and wisdom in pilgrim visitors' books.

At the moment I'm going through a huge bibliomaniac phase. I'm reading library books rather than buying books. I tend to read books in different ways and at different speeds, depending on the form, the content, the style, the density, the difficulty. I've no problem reading some books in a day and others in a year. War and Peace, In Search of Lost Time and The Alexandria Quartet still lie unfinished on my shelves, though I love these novels more than I can say. I also have no problem reading some books twice, some poems countless times and some texts not at all. Life's too short to feel you have to read certain books just because you think you ought to or because others have praised them.

Having said this, I'm lucky in that I do seem to have a wide taste in subject and styles, and, strangely, this compass is getting wider the older I get (you might think this would be the reverse). I don't read books simply for 'escape' or 'entertainment', though I realise that most people do (I hasten to add that I've nothing against this, naturally, and am in no way an intellectual snob). I read to be moved, enlightened, educated, inspired, transformed. Although I've travelled quite a bit, books take me much further than my feet will ever take me. Books really do enlarge and stimulate the mind, and provide the hope, beauty, joy and consolation so necessary for us all.

As examples, let me take two library books I've just finished with. If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things is a debut novel by Jon McGregor, which was first published on 2002. I remember the sparkling reviews at the time. But after reading the first few pages, and then skimming through it, I really could not bear it. He writes of ordinary life in an ordinary street in an ordinary town. But it's hard to write interestingly about everyday life and, for me, he doesn't quite achieve it. I also could not stomach the pseudo-Beat or Whitmanesque style of the opening paragraphs:

And all these things sing constant, the machines and the sirens, the cars blurting hey and rumbling all headlong, the hoots and the shouts and the hums and the crackles, all come together and rouse like a choir, sinking and rising with the turn of the wind, the counter and solo, the harmony humming expecting more voices . . .

I found this too general, too contrived, too artificial. I prefer something more specific and gutsy. But that's just me — one's taste is so personal. Many people really did love this novel.

Turning now to Rob Cowen's Common Ground, I came across this book serendipitously in a local library. I'd never heard of it before. It came out last year and focuses on a small triangle of edge-land — borderland between town and country — in Bilton, a suburb of Harrogate. I read it quite slowly — you are forced to, as the text can be densely textured (though not difficult) and startlingly, dazzlingly metaphorical. It's staggering, thrilling writing about the symbiotic relationship between man and wild animal. Cowen manages to convey both the crude blandness of life — with its sewage works, factories, chip shops and traffic — and the magic of nature in this ordinary yet extraordinary corner of England. The mundane and the mystical coexist side by side, and he creates something truly wonderful out of this apparent dichotomy. Cowen is without doubt one of our best current writers on landscape, on a par with Roger Deakin, Richard Mabey and Robert MacFarlane.

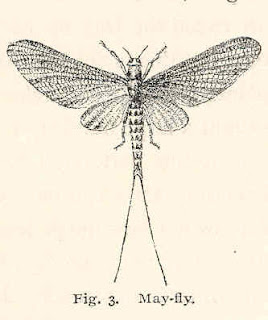

In this passage from his book Cowen writes about the brief life of the mayfly:

Time is of the essence and yet there is no sense of time. Not as we know it. No fear of the coming, inevitable unknown; these are prehistoric creatures of the present, 300 years in the making. An order older than dinosaurs. Time to them is in the frequencies of the surrounding birdsong, the fluttering of wings, the sun moving through the foliage, the colours that move across their compound eyes, the vibrations that spill down from a passing heron's croak. Light spills down too, a hot afternoon light that fractures the wood, falling in shards between trees and water. The infinite motion of the river runs in one direction; the endless flux of sky meeting wood in another, and into this strange dimension, as though an irresistible force possesses them, the spinners* rise on stained-glass wings, like angels.

And here he considers the importance of the countless, tiny, overlooked miracles to be found in the the natural and not-so-natural world:

These long days. These late-summer days, immense and golden. It's Tuesday. I walk up the lane at lunchtime troubled by the thought that I may have been lax in my own recordings of this place. The microscopic details of the here and now seem to possess an inexpressible value that I'm worried I've overlooked. I wish I'd kept more rigorous data. More snapshots. The changes in a single leaf in a single location from day to day.The biodegradation of a discarded fag butt on the stone track. The minute-by-minute movement of a single bird through the wood. Maybe these are the things of true importance.

* 'Spinner' is a name for the adult form (imago) of a mayfly.